Download: Story Sketch Template

When I begin any new writing project, a sketch is almost always the first thing I do.

That's because a sketch can be anything you need it to be. A lot of times, I will have a one-sentence idea come to me--just the barest notion of what I want the story to be about--and I'll open a sketch template, and jot it down.

Other times, I'll have a random idea that's not connected to anything specific. Sometimes it'll be an idea for a scene, or a character, or it might be a line of dialogue. Typically, I jot these little tidbits down in Google Keep, and then, next time I'm at my computer, I'll browse through my folders and see if I have an existing story idea I can attach the new idea to. I'll copy-paste it into the sketch, and then I can forget about it until I need it again.

As a writer, most of the little tidbits and micro-ideas we come up with will go unused. But it's good to get in the habit of writing everything down, because you never know when you've hit on the tip of an iceberg. Sometimes the smallest ideas can become portals to new dimensions of creativity. A few words could come to define the rest of your career, just like they did with me.

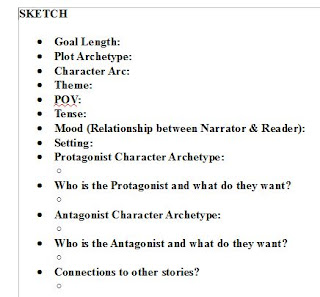

The Sketch template exists to help you organize these random tidbits. It's first and foremost a catch-all for ideas, but this template also includes some guidance for defining the outlines of any new story.

One of the first questions to ask yourself, once you start getting organized is "How long do I want this story to be?" It's a seemingly simple question that can drastically affect how you approach a story. If the idea is substantial, you might want to set the goal at traditional novel length (80-100k words), and then you know you need to spend some time developing settings, characters, and wrangling the idea into some kind of story structure. If the idea is simple, you might want to make it a short story, and not waste too much time on background.

If you believe in the power of archetypes like I do, choosing a Plot Archetype is an important step. If this step isn't important to you, just delete it.

Character Arc, however, should be important to every writer. A story without some kind of character arc isn't really a story, it's just a series of events. Whether you choose Positive, Negative or Flat, the Sketch template is a good place to jot down some basic ideas about what change your character will go through.

Theme is another area that might or might not be important to you. Sometimes, I find the theme is the starting point for a story. For example, you might think to yourself "I want to write a story about domestic abuse." If so, I recommend opening a new Sketch template, writing "domestic abuse" under theme, and going from there.

Point of View is one area that's not always clear from the outset, but I find if you spend some time thinking about it beforehand, you can save yourself a lot of trouble. Tense and Mood are a part of POV, so I've grouped these items together.

One of my works-in-progress began its life as an unconnected chunk of narrative. I didn't know who was saying it, or what it was connected to, but I wrote it down, and I started developing the story. In general I prefer an intimate third-person POV, so I started writing the story that way. But the chunk of narrative that had inspired the story had no place in a third person POV, because it was in a conversational style, and third person is less than ideal for conversational narrative. In my current draft of the story, I've re-cast the narrative into first-person past tense, which shows us an older, wiser protagonist looking back on the events of the story. This change allowed me to use the conversational narrative style, while giving the actual plot events a degree of perspective that was missing from the original draft.

So when you start plotting a story, think about what POV gives you the right ratio of intimacy or perspective. A character study like Catcher in the Rye is best told with a lot of intimacy, hence the choice of first-person. But a story of society's path to revolution like A Tale of Two Cities, needs a broader perspective, which is why Dickens' choice of an omniscient POV works so well. So figure out how big your story is, and choose the POV that fits it best.

Mood, with respect to this document, simply means the relationship between the reader and the narrator. Straight third-person narrative is written in a voice that has no awareness of the reader, whereas a jocular omniscient like the one Douglas Adams favored is dependent on awareness of the reader. The reason I've chosen the term Mood is that the narrator's feelings about the story greatly affect the way the story is told. If an older, wiser narrator is telling a story about the indiscretions of his youth, that will color his descriptions and depictions. If we are living the story in real time with a first-person present narrator, the narrator's emotions will rise and fall with the emotions of the scenes. If we're reading a Douglas Adams novel, the omniscient narrator's irreverent attitude paints everything in bawdy colors. SO there are good reasons to choose any POV, just make sure you're choosing the one that's right for your story.

Setting is another thing to consider--both time and place. It's also a frequent entry-point to a story. Sometimes I'll say to myself "I should do a story on Mars", or something like that, and I develop the story from there. Other times, the choice of setting depends on what kind of story you want to write. Say you're doing a love story. Love stories are best when lots of people can identify with them, so chances are an everyday location will suit your needs. But maybe you want to do something different, and set it in war time? Or on the moon? The choice of setting can take a fairly archetypal story in a new direction.

The next few items deal with Character Archetype, and they may or may not matter to you. Personally, I always try to find the Greco-Roman deity at the heart of my characters. These images are powerful and enduring, and I find them a useful guide. But not everyone agrees with me here and that's fine.

One thing is for sure: you probably want to have some idea of who your protagonist and antagonist are before you start. So it should be fairly obvious why the question of "Who is the [Protagonist/Antagonist] and what does s/he want?" is important.

Beyond those areas of guidance, this template is open season. Any and all ideas should be thrown here before being digested into other notes, or the manuscript itself. Once they've been addressed in some way, they can either be deleted, or moved under the "Notes Addressed" heading. Personally, I never delete notes unless I think they'll confuse me later, and I like to have a record of my thought process so I can backtrack if I need to (I never have, but better safe than sorry).

...

Overall, this template is a simple thing, but hopefully it contains enough guidance to get you thinking critically about your story. It also serves another important function though: it can help you decide when a story isn't ready to be written. A lot of times, I'll start filling out this document, and discover there's a major subject I need to explore before diving into the drafting process. In that way, doing a detailed story sketch can keep you from wasting time.

Either way, I hope you find this template useful!

No comments:

Post a Comment