But I firmly believe that every story--short or long, comic or tragic--makes some kind of argument, whether it intends to or not. Perhaps that argument is of great import, perhaps not. But just because it isn't groundbreaking doesn't mean it's not there.

My final year in high school, I was on the debate team. Within a few weeks of the class, I knew I should have been in debate my entire high school career, but unfortunately I came late to that party. Such is life.

In that class, we learned about a tool called an Argument Map, which looks like this (also, look upon my amazing Microsoft Paint skills and despair):

I like this model because it is super intuitive. Let's have a quick look at the parts.

- First, you have your Proposition, phrased in this model as a yes or no question. It is the foundation of your house. [If you use this model during plotting, and can't think of a way to phrase your question as a yes or no, any binary (either/or) question will work.]

- Second, for the roof of your house, you have your Conclusion, phrased in this case as a yes or a no.

- The walls of your house are Assertions, and there can be as many as you need. These support your conclusion.

- Each wall has slats holding it up, and these slats are your items of Evidence. Again, you can have as many as you need.

- The ground beneath your house is made of your Assumptions, which underlie everything you argue and assert.

- Finally, the little weather vane on top is the Implications of your argument. It is what necessarily follows from the conclusion.

Forgive this nerdiness, I'm super into logic. Came down with a wicked case of Philosophy Major when I was in college.

The point of this model is that it allows you to visualize arguments in such a way that you always know where to attack them. And with this tool, you can literally dismantle any idea conceived of by the human mind.

If you can discredit the evidence surrounding the assertions, you can knock the house down quite handily. But if that's not possible, you can always attack the underlying assumptions by proving they are flawed, or you can attack the implications by proving they are disastrous (hint: we see a lot of these last two strategies in politics, and precious little refutation of evidence)

If every story contains an argument, then this model can be useful in making decisions about theme. The Story Argument's proposition is the theme.

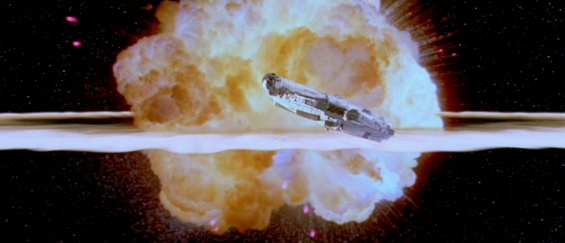

Find a way to phrase your story as a yes or no question. Let's use Star Wars as an example, and let's pretend for the sake of argument that Episode IV was a self-contained story, and not an installment in a more complex series.

Find a way to phrase your story as a yes or no question. Let's use Star Wars as an example, and let's pretend for the sake of argument that Episode IV was a self-contained story, and not an installment in a more complex series.

What is Star Wars really about then? If you ask me, it's about Luke discovering that an ordinary country boy like himself can become something more, be part of something greater, and make a meaningful difference against the oppressive Empire. So here's a crack at the proposition:

Proposition: Can an ordinary country boy make a difference against an oppressive regime?

We know that Luke ends up destroying the Death Star, so I suppose the answer is yes. So now we have our conclusion. [If you don't know the end of Star Wars, I have a question: what color is the sky in your world?]

What assertions support this conclusion? How about the fact that Luke single-handedly destroyed the Empire's greatest weapon? That's pretty good one.

But what happened before that? Luke, Han and company rescued Princess Leia from the Empire's clutches. And over the course of their entire interaction throughout the movie, Luke convinced Han Solo, a self-centered smuggler, to join the battle.

Seeing a pattern? Every major arc and sequence in your story can be thought of as an assertion that supports your conclusion.

And they have evidence to support them too. Luke's destruction of the Death Star was supported by his efforts to learn the ways of the Force. His daring rescue of Princess Leia was supported by the efforts of the friends he made along the way. And his unwavering belief in the Force and the Rebellion eventually led to Han's decision to join a cause greater than his own survival.

Assumptions and implications typically only come up when an argument is being attacked, but just for fun, what are some assumptions and implications that underlie our Star Wars argument map?

One assumption that's up for debate is that the Empire is oppressive. It could be argued that the Empire is in fact the best thing for the galaxy at the moment. Another assumption is that Luke is just an ordinary country boy. As we find out in the most famous scene in The Empire Strikes Back, Luke is anything but a simple bumpkin; he's the descendant of one of the most powerful Jedi in history. [If you think I should have written spoiler alerts for this stuff, you should be tarred and feathered.]

And the implications of the story are what gives rise to the sequels. Destroying the Death Star may have been a strategic and symbolic victory for the Rebellion, but it did not destroy the entire Empire, so an armed response was inevitable. The implication of the Story Argument is that the Rebellion will face even fiercer opposition going forward, and one could argue that's reason enough to avoid attacking the Empire.

Hopefully you can see how this model of argument can inform your decisions on theme in your story. Even if your theme is a relatively banal, like "Is love possible?", this method can help you make sure your story argument holds together.

Every story contains an argument, even if it's relatively familiar. And it's okay for a story argument to be familiar. There are certain lessons audiences will never tire of learning (love conquers all, justice exists in this world, ordinary people can do extraordinary things). But familiarity is no excuse for flimsiness.

...I'm gonna go watch Star Wars now.

No comments:

Post a Comment