The Midpoint Sequence advanced the protagonist into a state of conscious competence; they now know what needs to change for them to reclaim a feeling of normalcy. They can't do it automatically, but with effort and concentration, they are able to act correctly. Act Three shows them taking deliberate, proactive steps towards achieving their goals.

Accordingly, the first scene you should plot in Act Three should show the character taking some concrete Action in response to what they learned in the Midpoint Sequence. This scene is similar to the reaction scene at the beginning of Act Two. It serves a similar function: to demonstrate the change in the protagonist's competence level.

Because the Reaction and Action scenes serve similar purposes, this is a natural opportunity to use what I call rhyming scenes. A rhyming scene is one that syncs up, mirrors or "rhymes" with a previous scene in some way. The similarity can be major or minor: a rhyming scene might take place in a similar location, or contain a similar line of dialogue, or present a similar series of events.

The purpose of rhyming scenes is that an element of sameness on the surface highlights the difference on a deeper level. For example:

Say you're writing a story about a workaholic inventor. He ignores his family, and stays locked up in his lab for days. Somewhere in Act One or Two, you write a scene where the hero's mentor character--say, his old professor--advises him to go to his son's baseball game instead of working.

Then in the Midpoint Sequence, the inventor's wife leaves him, and he spends the Mirror Scene wondering why his inventions always take precedence over his family.

A good rhyming scene for this story might show the now-reformed inventor talking to his sidekick--say, the lawyer that helps sell his inventions--and advising him not to miss his daughter's dance recital.

Okay, that example isn't very deep (sorry, it came off the top of my head!), but you can see how an element of sameness in the situation highlights the difference in the character.

Rhyming scenes are a great way to show character growth. They can go nearly anywhere in your story, but the beginning of Act Three is a great opportunity to throw one in.

Another opportunity for a rhyming scene is in the second Pinch Point. Just like in Act Two, readers are hard-wired to expect some kind of maneuver from the antagonist about halfway through Act Three, roughly 60-65% of the way through the overall story. Because you have another Pinch Point back in Act Two, you could easily craft a rhyming scene at the same point in Act Three.

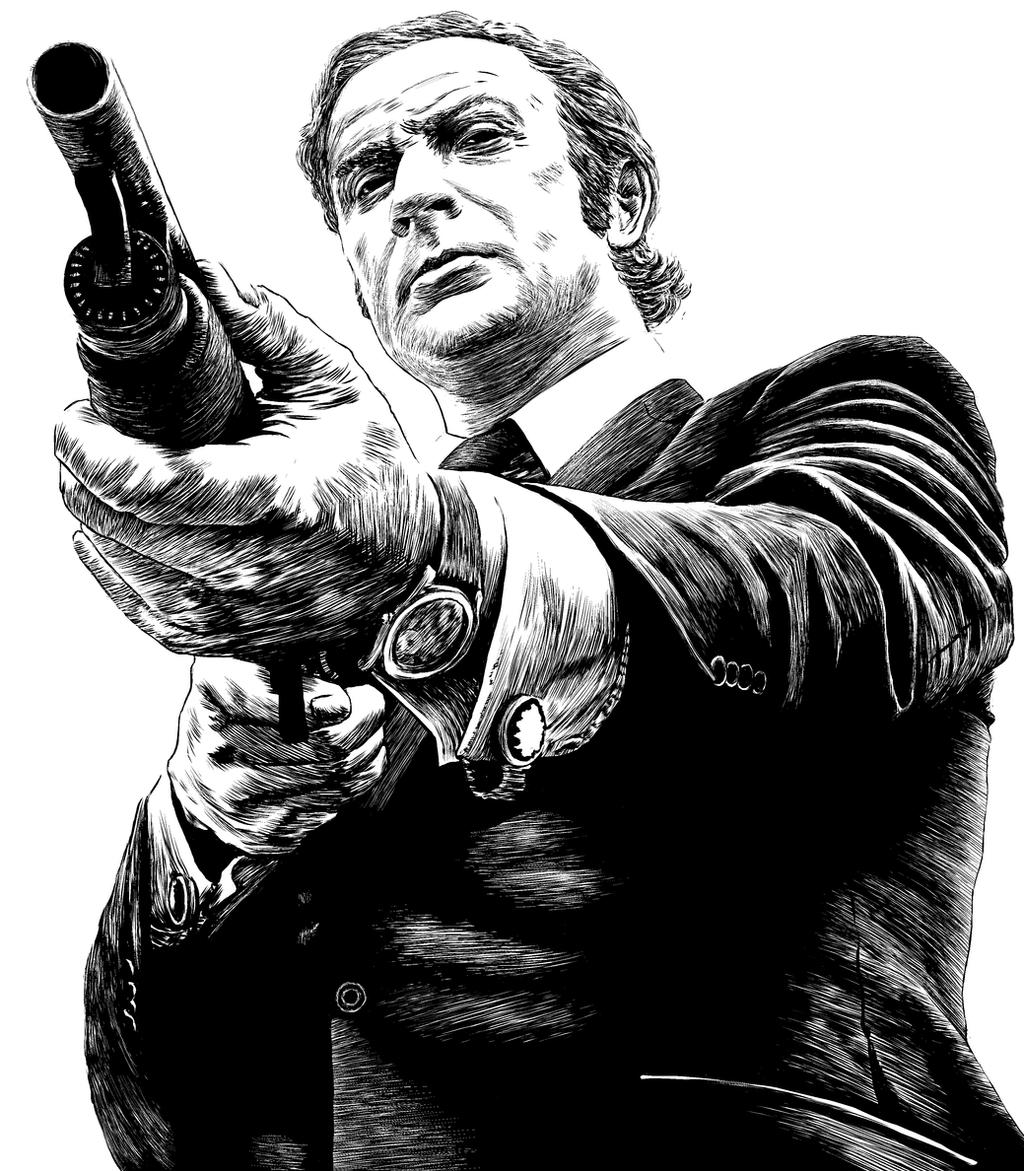

Still another opportunity is in what James Scott Bell calls the Pet the Dog scene. This scene is optional, and a lot of stories don't include it, but I find it useful. The Pet the Dog scene mirrors the Save the Cat scene; it's a reminder of why we're rooting for the character. JSB's example is the point in The Fugitive where Richard Kimble changes the charts for the injured kid and saves his life. It reminds us that Kimble, despite what he's done to evade the cops, is a basically good guy who got framed.

Another optional scene I like to use is the False Victory. K.M. Weiland makes a good argument for this in her series on story structure. Act Three shows the character in a state of conscious competence, but we can't make things easy for them, or the tension disappears. Showing your character achieving some goal, only to find out that it was meaningless or misguided, helps keep the pressure on.

The last ingredient I encourage you to use in Act Three is the Thing The Hero Needs scene. This scene is a natural mirror for the Argument Against and Argument For Transformation scenes, because it bluntly spells out the change the character needs to make. By the time you get to Turning Point Three, you're going to be ratcheting up the pace and tension, and you're not going to want to spend too much time on character arc ruminations like this. It's good to spell this out as directly as you can without knocking on the Fourth Wall, that way readers go into the final phase of the story knowing exactly what the stakes are.

Properly used, any of these scenes can demonstrate conscious competence. Rhyming scenes easily highlight character growth. A Pet the Dog scene can show the character's good side re-emerging from the chaos of conflict. A False Victory can show the character that the goals their old goals are no longer meaningful. And when the hero encounters the Thing s/he Needs scene, they take another step into conscious competence.

Next, we'll examine Turning Point Three, which threatens to undo all this progress.

No comments:

Post a Comment